Wired notes that on this day in 1903 Thomas Edison electrocuted an elephant to death as part of his smear campaign against alternating current, a system in competition with his patented direct current system. As the War of Currents raged, Edison grew increasingly alarmed at the acceptance of AC as the electrical distribution standard, and so set out to scare the public into believing it was too dangerous through a series of publicized animal executions using AC. Topsy the elephant was merely a notable exception in a long string of fried dogs and cats. (Edison also promoted the use of an AC electric chair for human executions, even though he was opposed to capital punishment; such was his desire to tarnish the image of a competitor at any cost.)

It should not surprise readers of this site that the decision that led to AC beating out DC came from none other than the Lord Kelvin.

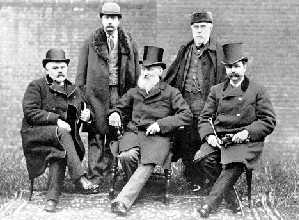

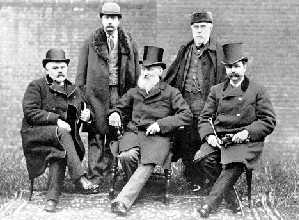

The International

Niagara Falls Commission, headed by Lord Kelvin (center).

It was Lord Kelvin who headed the 1895 International Niagara Falls Commission that chose Nikola Tesla's alternating current system over other proposals, including the Edison-backed DC system from General Electric, and awarded Westinghouse the contract to construct the hydroelectric generators at Niagara Falls. This highly-visible project showed the practicality of the system and turned the tide in favor of AC.

Kelvin had originally been opposed to alternating current before being swayed at the 1893 Chicago Exposition. His acceptance of Tesla's system actually completed a circuit, since an inspiration for much of Tesla's research was Kelvin's 1853 paper "On Transient Electric Currents". Kelvin, who had long been a promoter of electric lighting -- his house in Glasgow was the first in the world to by fully lit by electricity -- saw in AC the potential to bring about a dream of his, that he reiterated on a visit in 1902 (quoted in The Post-Standard, April 22, 1902, p. 1):

It has been so great, so marvelous, that I hope to live to see the day when a dream I have had may come true. I fervently hope to see the day when we shall have the transmission of electric power over 300 miles with a voltage of 40,000. When I first talked of that fifteen years ago I was laughed at. But with the wonderful transmission of power at Niagara Falls, my dream looks to be near fulfillment in the close future.

And let me tell you American people, there may be a time when the waters will flow no more over that great horseshoe, but instead there will be a beautiful growth of vegetation far more superb than any water flowing in torrents over the precipice, water that will find its way down countless turbines spreading light and power for hundreds of miles in all directions.

Edison's use of violence against animals to undermine Lord Kelvin's choice of AC was viciously ironic given Kelvin's concern for animal welfare. Kelvin, who was a vice-president of the Society for the Protection of Animals Liable to Vivisection, publicly spoke out against animal cruelty. While he did allow that some vivisections might be necessary for the advancement of science in cases where new knowledge might be gained (he later resigned as SPALV vice-president when the Society united with the more hard-line International Association for the Total Suppression of Vivisection,) he firmly held that repeated vivisections merely for the edification of students was "altogether unnecessary" (source).

In a letter to the Scotsman on March 6, 1877 (quoted in S.P. Thompson's The Life of Lord Kelvin), he wrote:

SIR—In your print of this morning I see a report of Professor Rutherford's paper on "The Secretion of Bile," read at the meeting of the Royal Society yesterday evening, when, as president, I was in the chair. As chairman I did not feel that I had the right to express my opinion that experiments involving such torture to so large a number of sentient and intelligent animals are not justifiable by either the object proposed, or the results obtained, or obtainable, by such an investigation as that described by Professor Rutherford. I feel this opinion very strongly, after many years serious consideration of the general question of the advisableness or justifiableness of experiments involving cruel treatment of the lower animals. I trust you will kindly give me this opportunity of expressing it, as my presence without protest yesterday evening might seem to imply that I approved of the experiments which were described.

As to electrocuting animals, this anecdote (recounted in The Elyria Chronicle, Aug. 1, 1906, p. 4) clearly shows that he was against it:

Lord Kelvin once performed a daring experiment before a class of students. In the course of his lecture he said that while a voltage of 3,000 or so would be fatal to a man a voltage of some 300,000 would be harmless. He was going to give a practical illustration on himself, but the students cried out, "Try it on a dog!" Lord Kelvin cast a look of reproach at his class. "Didn't I figure it out myself?" he said quietly, as he walked to the apparatus and safely turned the tremendous voltage into himself.

Kelvin's fondness for his pet parrots, Doctor Redtail and Professor Papagaio, was typical of his concern for animals. S.P. Thompson notes:

Lord Kelvin was very fond of animal pets. His parrots have several times been mentioned. He had a horror of unnecessary slaughter of creatures, particularly of birds. He once seized the arm of a man who, while on board his yacht, was shooting a sea-gull, and he protested indignantly against such wanton cruelty.

In contrast, Edison's proclivity for animal abuse extends even to his arrogant self-promotions, as can be seen in Garrett P. Serviss's Edison's Conquest of Mars, an 1898 sci-fi newspaper serial that was officially authorized by Edison's PR machine. The story, which coincidently casts Lord Kelvin as a supporting player, contains the following scene that would have disturbed Kelvin:

TESTING THE "DISINTEGRATOR"

I had the good fortune to be present when this powerful engine of destruction was submitted to its first test. We had gone upon the roof of Mr. Edison's laboratory and the inventor held the little instrument, with its attached mirror, in his hand. We looked about for some object on which to try its powers. On a bare limb of a tree not far away, for it was late fall, sat a disconsolate crow.

"Good," said Mr. Edison, "that will do." He touched a button at the side of the instrument and a soft, whirring noise was heard. "Feathers," said Mr. Edison, "have a vibration period of three hundred and eighty-six million per second."

He adjusted the index as he spoke. Then, through a sighting tube, he aimed at the bird.

"Now watch," he said.

THE CROW'S FATE

Another soft whirr in the instrument, a momentary flash of light close around it, and, behold, the crow had turned from black to white!

"Its feathers are gone," said the inventor; "they have been dissipated into their constituent atoms. Now, we will finish the crow."

Instantly there was another adjustment of the index, another outshooting of vibratory force, a rapid up and down motion of the index to include a certain range of vibrations, and the crow itself was gone—vanished in empty space! There was the bare twig on which a moment before it had stood. Behind, in the sky, was the white cloud against which its black form had been sharply outlined, but there was no more crow.

Furthermore, The Edison Papers' chronology page has this bizarre entry for April 6, 1877, suggesting the kind of violent work environment Edison fostered: "Laboratory staff's 'pet' bear gets loose and they kill it."

While I can find no record of Lord Kelvin commenting on Edison's public animal executions -- perhaps because Kelvin did not wish to appear biased, as with the incident in the Scotsman letter -- I find it hard to believe that he would have viewed Edison's elephanticidal barbarity, which contributed nothing to the advancement of knowledge, with anything less than abhorrence.

In the end, Edison's scare tactics didn't work; AC won out and elephants now know they have more to fear from monorails than from alternating current.