In a previous post on olive-eating tree octopuses, I mentioned octopuses from Palau that are supposed to give birth in trees. I didn't have access to the cited source of that claim, and the details given were scant, but I have found some older reports of arboreal octopuses from the region.

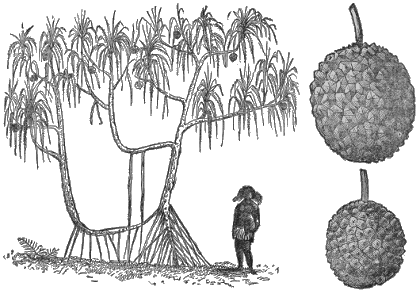

Screw-pine, or ara.

Throughout Polynesia is found a species of tree known as the screw-pine (Pandanus odoratissimus), or by one of its many native names, the ara. It can reach a height of forty-five feet and can grow near the water, although it's also found on hillsides. Islanders have many traditional uses for it: its wood is used for buildings and making walking sticks; hooks on the leaves for shrimp angling, and the leaves themselves for thatching and garments; and it has large, edible fruit. But the ara is particularly renowned for its fragrant flowers, which are used to scent cocoanut oil or are threaded and worn as perfumed necklaces.

In his books, Life in the Southern Isles (1876) and Myths and Songs from the South Pacific (1876), English missionary William Wyatt Gill reported that octopuses would come out of the water and climb the ara trees "for the sake of the sweet-scented flowers and fruit." In his Jottings from the Pacific (1885), Gill notes that "The octopus, doubtless attracted by the fragrance, climbs up the screw-pine to feast upon the flowers." He justifies this claim with a self-referential quote in a footnote:

Mr. W. Wyatt Gill, in his valuable and interesting book on the Pacific, Life in the Southern Isles, stated that the octopus occasionally climbed trees to eat the fruit. Mr. Henry Lee, F.Z.S., an authority on this class of animals, thought Mr. Gill must be mistaken in this statement, as no one had hinted at such a thing except old Aristotle. He asked Mr. Gill to make inquiry on returning to the Pacific. Mr. Gill has sent a letter fully confirming his previous statement, attested by many native eye-witnesses, students and missionaries, who had no object in inventing such a story. The tree is a species of pandanus, of which there are three representatives in the Hervey group of islands [Cook Islands]. The screw-pine (Pandanus odoratissimus) has scented flowers on the male tree and hard fruit on the female tree. It is for this flower that the octopus climbs, attracted probably by the scent. [...]

Pandanus, or Screw Pine, & Pandanus Fruit.

In The Tonga Islands and Other Groups (1890), Emma Hildreth Adams specifically marks the islands of Rakahanga and Manihiki as being popular ara-buffets for octopuses:

It is on both of these low coral islands [...] that the terrible octopus, having left the sea, travels over the sand and rough coral, to feast upon the fragrant and sweet-tasting flowers of the pandanus tree.

[....]

Attracted doubtless by the dense odor of the flowers, the strange octopus often leaves the sea, climbs the ara, and feasts upon them. This remarkable act of the cuttle-fish ["octopus" and "cuttle-fish" were used as synonyms prior to the 1900s] has been observed many times by both natives and missionaries.

According to The Caroline Islands (1899) by Frederick William Christian (who also reports on the octopuses' arboreal tendencies), the ara is known in Japanese as tako-no-ki (タコの木), or "the tree of the octopus". Whether it was given this name because of the octopuses' fondness for it or because the tree's tufts of leaves coincidentally resemble octopuses is not mentioned.

However, that resemblance does suggest that what might have originally attracted these octopuses to the ara trees was not the scented flowers -- which octopuses would have trouble smelling outside of the water, not having air-adapted noses -- but rather the appearance of fellow cephalopods frolicking in the branches. Spying these mirages from the tidepools, the first octopuses bravely journeyed into the Great Dry to see what all the hubbub was about; and what could have been a foolish mistake instead serendipitously led to their tasty discovery. Like the Lotophagi of Greek mythology, these Ara-Eaters might have lost all interest in returning to their watery home, wishing instead to stay in the tree tops eating the heavenly ara flowers.

I've been unable to find more current references to these curious cephalopods. Could it have just been a passing food-fad among some non-arboreal octopuses? or could a unique species of Polynesian tree octopus have gone extinct, like so many other island species unable to cope with habitat loss and invasive species? Perhaps, if we're lucky, the Ara-Eaters can still be found on some forgotten atoll, lazily munching away, unconcerned about their fate.

If you're in Polynesia and have any sightings to report, let me know.

Late addition: Here's an earlier report from an article in The Friend (Oct. 12, 1873):

At Manihiki and Rakaanga and many other low coral islands lying about four hundred miles from Mangaia, the poulpe or sea-spider [octopus] is accustomed to leave the sea and travel over the sand and broken coral to climb the pandanus-trees which grow on the beach, in order to feast upon their sweet-scented and sweet-tasted flowers and fruit. At dawn these curious fish may be seen in clusters on the outspread branches of the pandanus thus enjoying themselves; but as soon as their sharp eyes perceive the approach of their enemy, man, they instantly drop on the stones beneath, and hasten back to their proper element.

Perhaps the arival of many more humans has scared the Polynesian tree octopus back into the seas?

CORRECTION: Palau and the Caroline Islands are in Micronesia, not Polynesia. Sorry for the geographic blunder. The Cook Islands, however, are in Polynesia.

UPDATE 2010-11-19: For more from Micronesia, see: Nicharongorong: Tree Octopuses of Micronesia.

UPDATE 2012-12-29: I acquired an original copy of Gill's Life in the Southern Isles.